When Oppenheimer premiered in 2023, audiences were struck by the raw, visceral power of its Trinity test sequence. Director Christopher Nolan—the director behind The Dark Knight, Interstellar, and Inception—made an audacious call: forgo computer-generated imagery entirely in recreating the most devastating explosion in human history. Instead, their team harnessed real-world methods to craft a cinematic moment both authentic and haunting. How did Nolan’s VFX team, headed by Andrew Jackson, and special-effects experts like Scott R. Fisher build this moment of cinematic terror—completely analog? What follows is a comprehensive behind-the-scenes exploration of the creative alchemy that made Oppenheimer’s atomic blast feel incandescently real.

Nolan’s Practical Philosophy

For Nolan, film must capture truth through tactile danger. He has long championed practical effects over CGI; to him, simulation is never as impactful as reality. He believed that no digital tool could replicate the unpredictable beauty and horror of real flame and molten metal. That conviction set the tone from the outset: the Trinity test would not be faked—it would be born of chemistry and cameras.

Nolan and VFX supervisor Andrew Jackson pursued a rule: no CGI-built effects. They did use compositing software to weave layers together, but each fragment—sparks, flames, ember clouds—was filmed practically. Jackson described the challenge as akin to capturing “real-world methodologies” in service of cinematic metaphor.

Thermite Sequences: Burning from the Bottom Up

The breakthrough came with thermite, a potent mixture of aluminum and iron oxide. When ignited, thermite burns at over 2,000°C, producing molten iron that drips like incandescent nectar. Working in a sandbox, Fisher’s team lit thermite inside a container so the burning iron would pour through a hole, generating miniature firefalls and detonation-like bursts. The result was luminous, unpredictable, and strikingly analog. Cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema captured these shots in Super 35mm at 50 frames per second, slowing the footage into flowing, molten beauty that suggested both creation and destruction.

These miniature molten waterfalls—small yet mesmerizing—became the foundation for what Nolan called the “quantum moment” of the explosion: the micro mirroring the macro, atomic detonation echoing in a single drop of glowing metal.

“Big-atures” and Miniature Scale Shots

Larger structures—sanity tents, observation towers, shockwave fronts—were built in miniature, often 1/8th or 1/12th scale but physically sizable. These “big-atures” offered control and detail while maintaining a sense of scope when shot with IMAX cameras. Some were twelve feet wide, but when filmed with forced perspective and at 48 frames per second using IMAX rigs, they appeared enormous.

Van Hoytema created custom IMAX lenses that recorded both detail and ambience. The team also experimented with rack focus, letting the glowing thermite pours blur into miniature tower silhouettes, capturing the Trinity test in stunning distortion—like an echo of atomic reality.

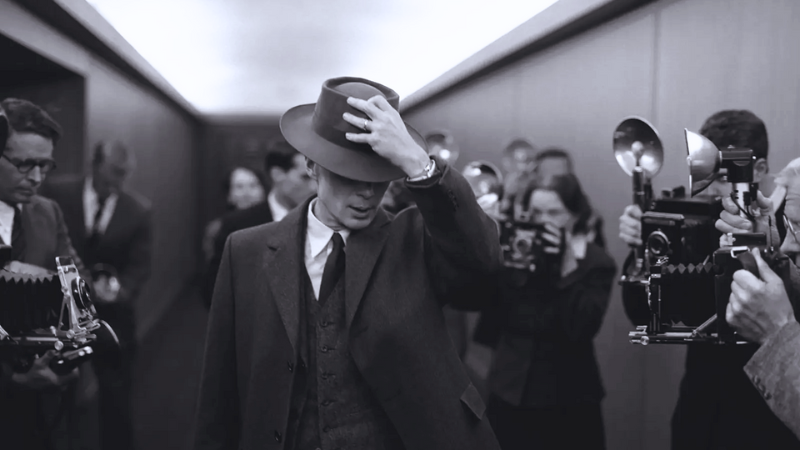

On-Location Build: Belen, New Mexico

Rather than filming at the restricted White Sands site, Nolan’s team recreated the surrounding bone-dry landscape in Belen, a desert plain south of Albuquerque. They built observation bunkers, earned weather unpredictability, and gave Cillian Murphy—playing Oppenheimer—the opportunity to experience the build-up. Murphy climbed a hundred-foot steel tower, paced in wind-blown dust, practicing safety protocols before the shot. When the flame erupted from beneath his vantage point, he truly felt the moment’s tension.

Nolan’s insistence on real desert conditions—heat, wind, inexplicable sandstorms—was critical. He believed the actors needed to sense their environment in real time to embody the dread of atomic power.

Compositing the Explosion

Even with all elements filmed practically, merging them demanded compositing artistry. Editor Jennifer Lame and DNEG VFX craftspeople layered molten iron pours, miniatures, dust clouds, and camera shakes into a cohesive whole. Jackson explained that fewer than 200 VFX shots were used, but each was grounded in filmed material.

Digital augmentation played a subtle role in extending shockwave fronts or enhancing embers. But the principle remained: every visual element was rooted in a real trigger. The film was meticulously stitched together, but it never sat on digital crutches.

Sonic Fusion: Sound and Score

Ludwig Göransson’s score complemented the explosion with absence of percussion and tribal rhythm. Instead, he used col legno strings—musicians tapping with wooden bow—to evoke tiny atomic tremors. Ticks, Geiger counter static, foot stomps, and hushed whispers built the suspense. On set, Jackson played test thermite footage for Göransson so he could tune the musical pace to match the fire’s heartbeat.

The result is that the Trinity sequence doesn’t just look primal; it sounds as if creation is imploding on itself. The score becomes a pulse of inevitability, echoing the widening ring of destruction.

Ethical Resonance in Real Flames

Nolan’s real-fire approach didn’t just craft shocking visuals—it forced ethical reflection. Analyses in Vox and EW highlighted how the visceral intensity reminded viewers that nuclear power is not a policy abstraction; it’s a moral rupture that ripples through humanity. By rendering the explosion with analog truth, Nolan brought that rupture physically into theaters.

In interviews, Nolan called the atomic sequence “a moment of reckoning.” He reminds audiences that Oppenheimer’s gain was our world’s loss. Watching real fire bloom on screen, we feel displaced, fearing not CGI spectacle but inherited ruin.

Safety Protocols and Controlled Flames

Fisher’s practical team treated thermite with deep respect. They constructed fireproof sandboxes, built six-foot safety berms, and stationed emergency crews at distance. Each blaze was started remotely with bears, timed ignition, and mandala-like choreography. Reports emphasize the sequence as one of Nolan’s most complex stunts—handcrafted heat—not cinematic spectacle.

Cast and crew watched from windowed bunkers or range towers. Cillian Murphy and Emily Blunt reportedly hugged each other as the fire flared upward. Nolan believes practical danger unites storytellers in uncertainty—and that unease becomes character.

From Micro to Macro: Visualizing the Quantum

Nolan intended the Trinity test to mirror Oppenheimer’s internal disintegration—his grief, his scientific obsession, his moral collapse. Catching glowing iron droplets is to glimpse atomic particles igniting reality. By filming miniatures in high frame rates and extreme close-ups, audiences perceive microscopic collisions as catastrophic waves.

StudiosBinder and VFX World highlighted how refracted superheated liquids, cloud tanks, spinning glass beads, and miniature debris became analog proxies for chain reactions. Each micro shot coalesces into an emotional flashback: watching a soul being reborn and irrevocably marred.

Collaborative Artistry: Light, Lens, and Tension

The Trinity scene was a symphony of contribution. Hoytema and Nolan developed IMAX macro lenses; Jackson and Fisher developed thermite tests; set and res team built bunkers; Lame layered visuals; Göransson created matching audio; editors stitched rhythm. Every department spoke practical language.

Nolan’s trust in craft came from years of working with veteran collaborators—from Wally Pfister in Memento, to Richard King on The Dark Knight, to Nathan Crowley on Dunkirk. His finest tools are human curiosity and analog instinct, not digital saviors.

Critical and Cultural Reverberations

When Oppenheimer grossed nearly $1 billion, critics praised the practical cinematography as a beacon of craftsmanship during a CGI-heavy era. Nolan’s real-burn stunts triggered conversations about nuclear normalization. Media critic Paul Schrader called the explosion sequence the most powerful visual of 2023. Others argued Nolan didn’t depict aftermath adequately—choosing philosophical terror over documentary fallout.

Still, Nolan maintained that his analog approach was essential to emotional storytelling. Nuclear weapons are living metaphors—not just visual chaos. If audiences felt urgency at the flash, it’s because reality was staring back.

The Aftermath: A Legacy of Practical Filmmaking

Nolan’s triumph may mark a turning point. Directors from Spielberg to Greta Gerwig have begun praising his risk. Some film students in post-production now carry thermite ideas in their notebooks. While CGI remains vital for impossible worlds, Oppenheimer proves analog can transcend spectacle—it can haunt.

Industry leaders note that practical effects costs can rival digital budgets. Bigature builds require material and labour; thermite and miniatures need controlled environments. But when the payoff is cultural resonance, the investment is cinematic insurance.

Burning Truth on Film

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer reminds us that some truths demand physical presence. The Trinity scene didn’t just show an explosion—it made viewers viscerally understand it. By using molten iron, filmed models, real flame, and silent dread, Nolan and his team elevated filmcraft into a moral medium.

In the annals of cinema, the Oppenheimer explosion stands not only as a technical marvel but as a moment when art confronted apocalypse with real fire. In doing so, Nolan reaffirmed cinema’s power not to distract—but to disrupt conscience and rattle the soul.